Dylan Vandenhoeck

What Do You See When You Close Your Eyes and Nod Yes?

October 30 - December 20, 2020

I stand in Dylan’s studio facing three paintings. On all three canvases, warped crystal ball landscapes sit enveloped in color.

On my left, a nighttime Manhattanscape hangs like a crystal necklace resting on dark velvet. Car lights beneath an overpass become jewels while a traffic light swings like a heavy treasure. In the corner of the painting, a silent scream of white mimics the kind of peripheral phenomena generated by moving my head in circles.

In the next painting, a row of suburban buildings bend around a telephone pole like a peaceful car accident, dragging a behind-my-eyelids red in its wake. Like the first painting, this scene is as much an inner landscape as an interpretation of a place. I keep glancing at the backlit houses because they look like the kind of image that will disappear when I look away, like a reflection on moving water.

Dylan’s arm emerges from the peripheral space into the middle of the third landscape; his body is a cup and his vision clear water. His arm, holding a palette of the very colors used to describe the field, is like a spoon mixing something into his drink. He is painting about painting because experience, especially in nature, becomes meta as forms fit into other forms and repetitions become patterns.

When I ask Dylan what he hopes someone looking at his paintings might feel, he says, “Different layers of experience are strange and difficult to trace.”

We don’t usually talk about what we see when we close our eyes and nod yes. It’s different every time, and so it makes sense that these different types of imagery—abstract, observed, remembered—fit together into one experiential image. I find myself accepting the combination, because I too remember what it’s like to close my eyes in a field, or to feel consumed by the night.

Dylan’s paintings propose an immersive, lived experience and ask me if I’m up for it.

Against the backdrop of a sociopolitical climate that is, as Dylan writes, “regressive on an existential level,” painting stands up for the notion of a “lived human experience” in the face of soundbites, echo-chambers, fake news, and our high-def, yet inarticulate, commander-in-chief.

In Dylan’s paintings, the gravity, or the ruler, or the decision maker, or the thing-that-unites-these-elements, is the feeling of being present. Disparate images and mark making work together to form the idea of a particular moment in time.

See how the trees bend to Dylan’s perspective like a gravitational force is pulling their crowns back toward earth. How the paint blobs in East Broadway collapse the signified and the signifier because paint, in the artist’s words, “captures the immediacy of what hasn’t yet been named”.

See how vast and colorful my response is to his paintings. Yours probably is too. When I ask Dylan what he wants from a viewer, he says, “I would hope they would turn away and notice their own version of this.” There’s a sense of communion to his answer that echoes the way his body and vision seem to melt together in these paintings. I’m struck not by the intimacy, but by the type of intimacy. It’s athletic.

I’m writing under COVID-19 quarantine—I am home, not sick, but not exactly well. Dylan’s paintings ask me to remember I am still whole, in my own skin, that I have memories, dreams, and reflections.

The paintings from the show remind me of running to the point of nausea, when exhaustion leads to a thought: you can articulate something without a name, but how? By being present in your experience. By participating in reality. By allowing an experience to change you.

- Sarah Esme Harrison

Dylan Vandenhoeck Chiasm / Afterimages, 2018/19 Oil on Canvas 84 x 74 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Chiasm / Afterimages, 2018/19 Oil on Canvas 84 x 74 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Chiasm / Afterimages, 2018/19 Oil on Canvas 84 x 74 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Chiasm / Afterimages, 2018/19 Oil on Canvas 84 x 74 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Chiasm / Afterimages, 2018/19 Oil on Canvas 84 x 74 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Chiasm / Afterimages, 2018/19 Oil on Canvas 84 x 74 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck What’s a Crop?, 2020 Oil on linen 28 x 24 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck What’s a Crop?, 2020 Oil on linen 28 x 24 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck What’s a Crop?, 2020 Oil on linen 28 x 24 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Mt. Kisco Walgreens, 2020 Oil on linen 66 x 41 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Mt. Kisco Walgreens, 2020 Oil on linen 66 x 41 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck East Broadway, 2020 Oil on linen 66 x 41 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck East Broadway, 2020 Oil on linen 66 x 41 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck East Broadway, 2020 Oil on linen 66 x 41 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck East Broadway, 2020 Oil on linen 66 x 41 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Jumprope/Anxiety, 2020 Oil on linen 36 x 24 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Jumprope/Anxiety, 2020 Oil on linen 36 x 24 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Plein Air Palette, 2020 Oil on linen 66 x 41 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Plein Air Palette, 2020 Oil on linen 66 x 41 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Plein Air Palette, 2020 Oil on linen 66 x 41 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Plein Air/Pressure Phosphene, 2020 Oil over casein on linen 24 x 18 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Plein Air/Pressure Phosphene, 2020 Oil over casein on linen 24 x 18 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Plein Air/Pressure Phosphene, 2020 Oil over casein on linen 24 x 18 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Co-op City, 2020 Oil on linen 66 x 41 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Running in Waveny Park, 2020 Oil on linen 66 x 41 inches

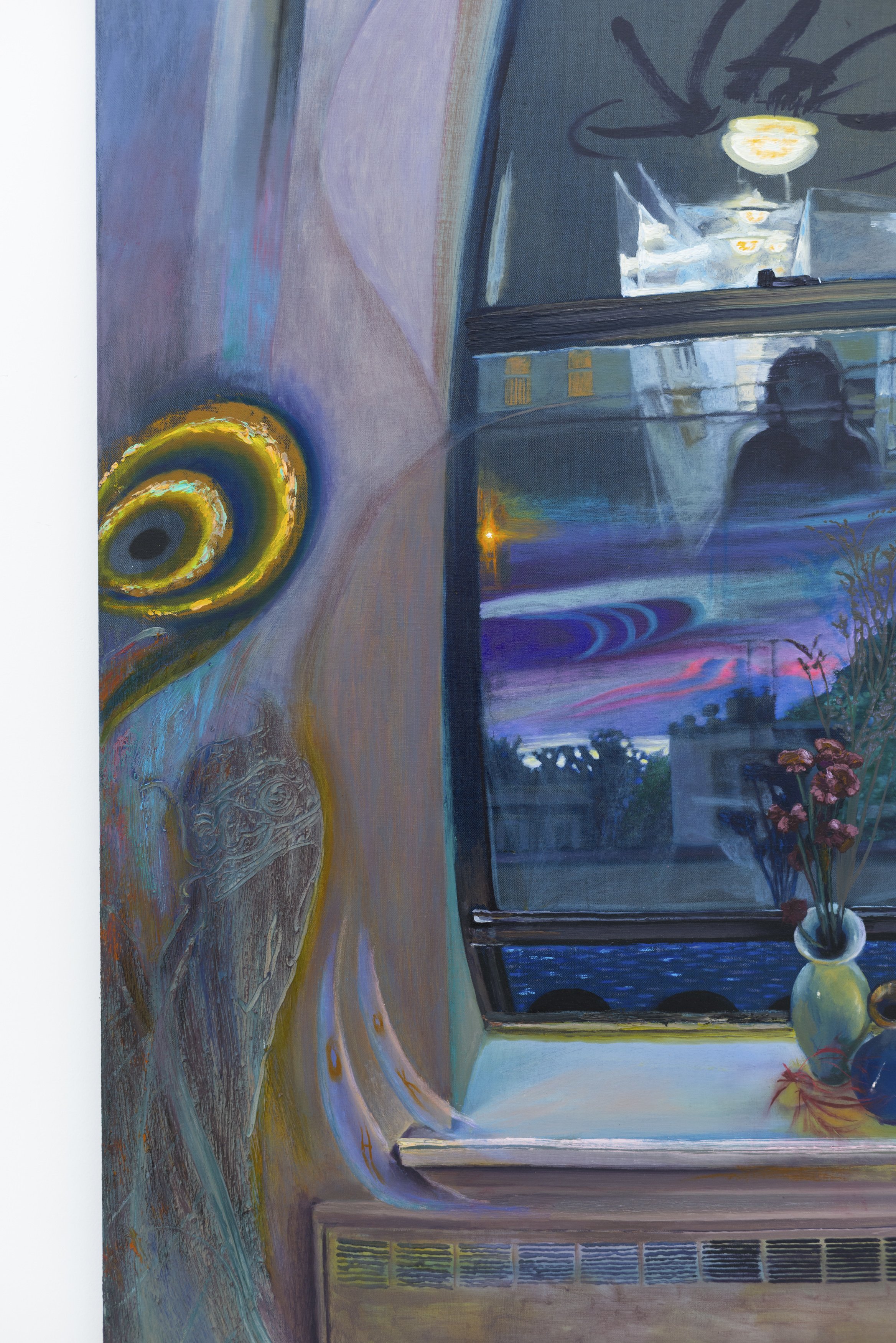

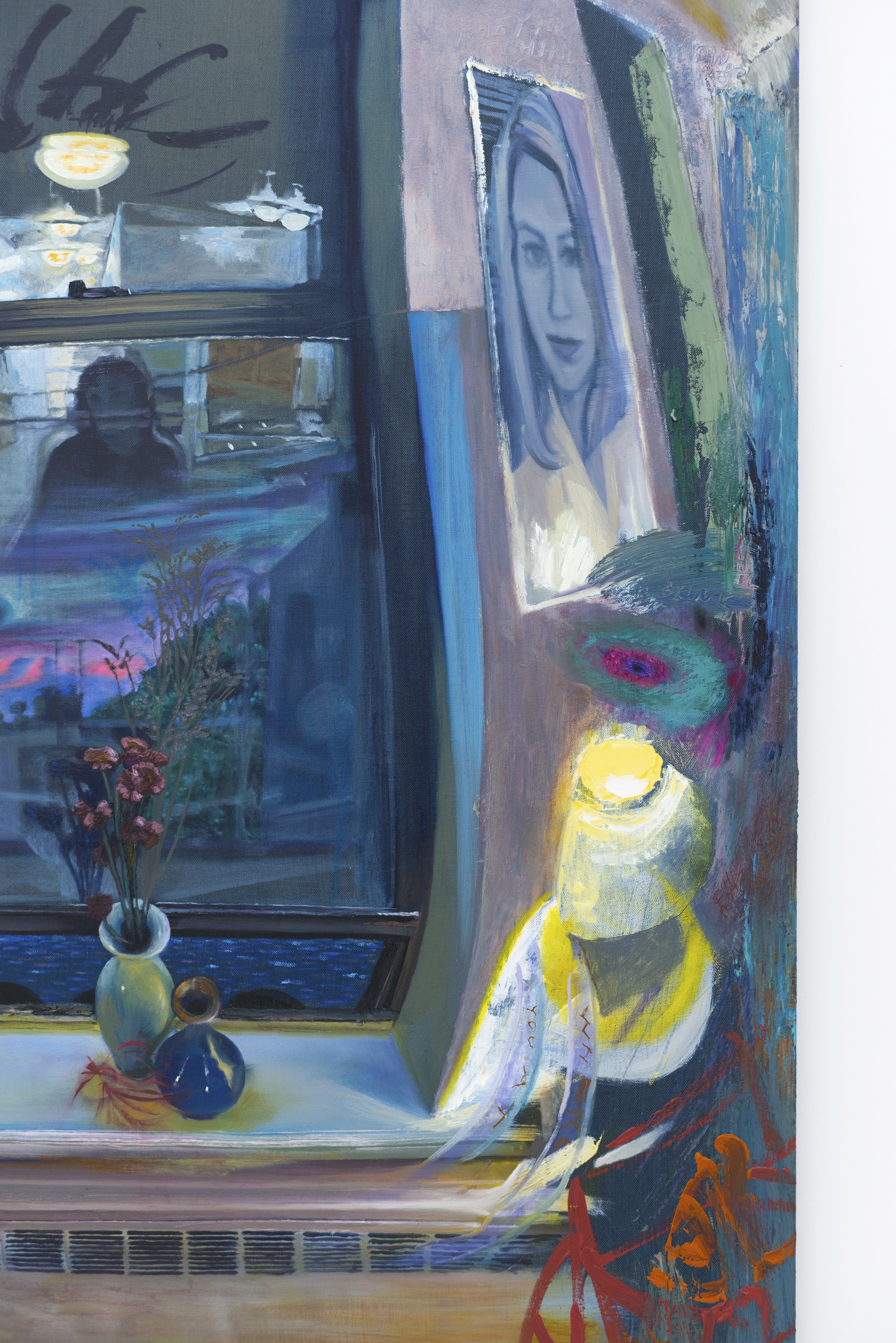

Dylan Vandenhoeck Window/Hallway, 2019 Oil on linen 78 x 44 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Window/Hallway, 2019 Oil on linen 78 x 44 inches

Dylan Vandenhoeck Window/Hallway, 2019 Oil on linen 78 x 44 inches